I’ve been pretty busy the last several days making and tubing a set of watercolors for myself. I had gotten 12 tubes from Daniel Smith recently and I wanted to make one paint for each of them.

I can’t guarantee perfect color accuracy from my scanner, but here’s the swatches for each paint I made. I really like the way Pozzuoli Red and Nicosia Green Earth look next to each other. The Shungite Black Ochre was different from the rest. When I was mixing it with the gum arabic I noticed patches of a slightly oily sheen on top of the liquid. I know that a pigment like lamp black is naturally oily, so maybe this one is too? I really like the paint it made though and I’m planning on making a painting with just this and maybe some of the titanium white.

Here are some things I would recommend for making your own watercolor paints-

• A basic recipe includes gum arabic, honey, and glycerin. It may take some experimenting to find a good balance of ingredients and to know how much pigment to use. Different pigments seem to require more liquid to avoid being thick and pasty, while others may become very thin and watery with the same amount of liquid added. I’m still experimenting to find a good balance, but most of these paints here I made with about 1 part gum arabic to 2 parts pigment, by volume, and a few drops of honey and glycerin.

• Start with a few inexpensive pigments, such as burnt sienna, so you can practice without worrying about the cost if the paint doesn’t work out well on the first few tries.

• Making your own gum arabic from a powder and some warm water costs less and is very easy to do. I mixed 1 part powder to 2 parts water by volume and got good results. Just let it sit in a jar for a while until it’s fully disolved.

• There are alternatives to gum arabic, such as dextrin, that may be cheaper and produce different results. I haven’t used it yet, but dextrin is supposed to make a thicker watercolor paint than gum arabic. I’ve also tried using peach tree sap and have gotten good results with that too. One of the best parts of making your own paint is that you can produce results that handle differently from what standard commercially made paint offers, so feel free to try different things.

• Mulling/grinding pigment with a glass muller on a glass plate is important for fully coating each pigment particle in vehicle, which in this case is the gum arabic/honey/glycerin mixture, as well as breaking down large conglomerates of pigment particles. Some pigments require more mulling than others.

• Until you gain more experience and confidence, avoid using toxic pigments. Most of the paints I made here are non-toxic, but even they would be bad to breathe in the fine dust of the dry pigment. Toxic pigments can pose a serious health risk in their dry form before being made into paint if they are breathed in. Wearing a dust mask would be a good idea when handling dry pigments.

Some advice for buying pigments-

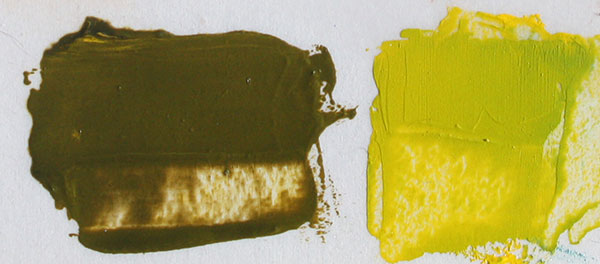

• Buying a larger amount of a pigment at once will mean a better price per gram, but it’s probably not necessary to purchase a huge amount of a pigment unless you know you’ll be using a lot of it. The two large jars in the first photo above contain one pound (453g) each of ultramarine (left) and mars yellow (right) from Blue Ridge that came in bags. I got them for an extremely good price, $14 for blue and $8 for yellow, but that might be more of those pigments than I’ll ever use in my life. Next time I think I’ll get half pound bags.

• Buying about 100g (weight) or about 4oz (volume) of pigment at once is a very good and common amount. It’s enough to make several tubes of paint with, so it’s cost effective when you consider the jar/bag of pigment probably cost the same or less than buying just one tube of pre-made paint, and it’s usually inexpensive enough in that size to buy several different colors to have more variety.

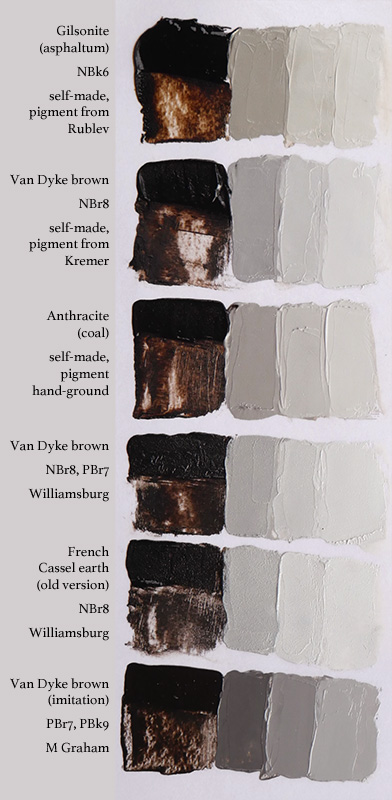

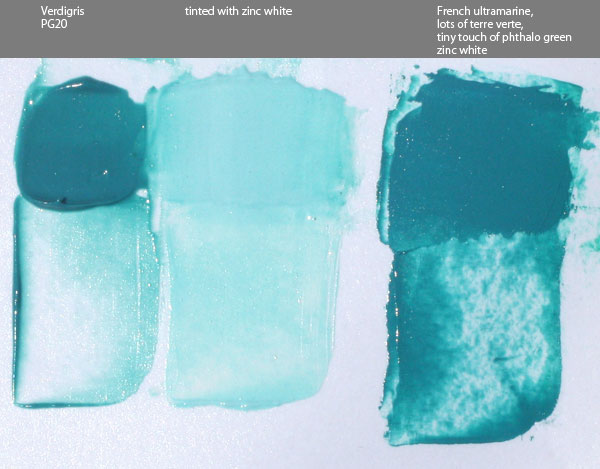

• Try finding unique pigments that aren’t made into watercolor paint by any brand. That way you can add these new paints to the watercolors you already use. For example, there are many varieties of natural yellow and red ochres, green earths, and both raw and burnt siennas and umbers but many brands of paint will only make one or two of each. There are also pigments used in oil paint that are also suitable for watercolor but that no one uses.

• There are many companies that sell dry pigments. You may find that one company sells pigment “A” for a high price and pigment “B” for a low price, but another company may be just the opposite. Some companies have high prices on all of their pigments. It’s a good idea to shop around and know what’s available. I found that Blue Ridge has some of the best prices on pigments, but the selection is a bit limited. They are available in 0.5 or 1 pound bags. Natural Pigments offers one of the largest selections of natural ochres, siennas, umbers, and green earths available in may different sizes, as well as other rare and specialty pigments. Daniel Smith has a limited selection of pigments available but only in 2oz jars or 1 pound bags. Some other companies that I haven’t ordered from yet include Kremer Pigments, Kama Pigments, Earth Pigments, and many other brands of paint that also sell the same pigments they use to make their own paint with.

• Remember that the point is to buy a pigment, not romance. Many paint makers sell their own pigments that they use to make their paint but at ridiculously high prices. They may be hoping that their brand name and reputation for making high quality paint will convince you spend $100 on a small jar of pigment that can be gotten elsewhere for $20. When looking at these pigments, ask yourself this- “After I make this into paint, will the final cost of materials for that paint be less than just buying a tube of the same paint from someone?” If the answer is no, then the pigment you’re looking at is priced too high. You should be able to make at least two or three tubes of paint from a small jar of pigment that’s the same price as buying it pre-made from a brand of paint.

• Of course, there are some rare pigments, such as lapis lazuli, that will cost a lot no matter who you buy them from and are not necessarily overpriced. It would be better to practice with cheaper pigments before investing in one of these.

This is a weekly pill box that only cost something like $1.50 I think. I wanted to fill each of the seven spaces with paint I made so I could take it traveling, but by the time I got the first two done I was getting tired of making paint and cleaning up after each color. Also I was almost out of paper towels from all that cleaning. The other five colors I just squirted into it from tubes that I bought.