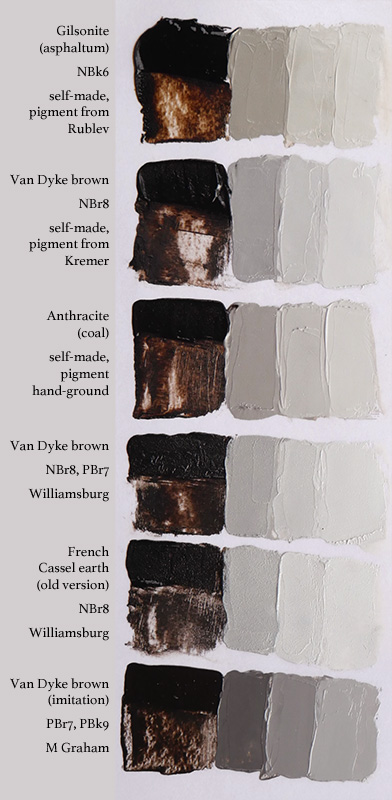

In this brief comparison I have a variety of unusual brown paints that each have long histories but are seldom used today.

Van Dyke brown is one whose name is commonplace even if the genuine paint is not. It’s named after Anthony Van Dyck, a famous Flemish portrait artist who made extensive use of it in the 17th century. It’s also known as Cassel earth because of the deposits of it near the town of Cassel, Germany, and carries the pigment designation NBr8 (natural brown 8) because it contains natural organic matter.

The last paint in the chart above is a modern imitation of Van Dyke brown. It’s actually a mixture of pigments – in this case burnt umber and ivory black – that only imitates the color but not the handling of the original pigment. There’s many other modern pigments and mixtures that also borrow their names from some historical pigment that’s either no longer used or is only rarely used, such as indigo, sap green, vermilion, etc. As is often the case, part of the reason to make a modern imitation is because it’ll have better lightfastness than genuine Van Dyke brown.

Although it obviously has much higher tinting strength than the other paints – the third tint is a 1:7 mixture with titanium white and is close to the 1:1 mixtures for all the others – it also loses its limited chroma very quickly when tinted to higher values. The Gilsonite and anthracite may be weaker tinting but they’re also much more chromatic at high values.

I also made an area, not shown here, of evenly spread test strips of each paint that I check each day to see how long it takes for each to dry. All of this was started nine days ago and as of the time I’m posting this only two have dried because most of these are slow drying paints. I’ll keep checking and update this when or if the others dry.

These three I made from dry pigment, using linseed oil from Rublev. Nothing else was added, and I don’t know for certain how well they’ll dry on their own. They probably could have benefitted from a little bit of umber (PBr7) being added, because that contains manganese and acts as a drier for oil paint.

Gilsonite is a bitumen-impregnated rock that’s mined in Utah, USA. Bitumen (NBk6), also called asphaltum, has had many uses since ancient times, such as waterproofing for boats and ships. Today it’s still used for things like road construction, hence the term asphalt. Another example of use is that Ford model T cars were black because they were coated in a laquer made from Gilsonite. There’s many other possible applications for it. This is the most chromatic of all the paints here, but I’m unsure of its longevity as bitumen gained a reputation in the early 19th century for causing oil paintings to crack.

Anthracite, a high purity grade of coal, was used along with lower grades of coal by some artists in the past as a black pigment. Almost three years ago I made some watercolor with it, seen here.

The tube of Williamsburg’s Van Dyke brown was given to me by Williamsburg a couple of years ago and is one of the two varieties of this pigment they offer. Only two other brands – Rublev and Vasari – make paint from genuine Van Dyke brown. It has raw umber in it, but just enough to decrease the drying time to about a week without having much impact on how the paint looks or handles. The test strip took seven days to dry.

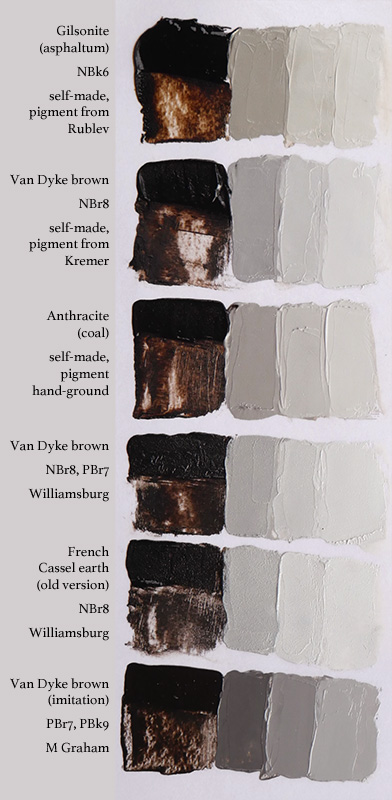

French Cassel earth is Williamsburg’s other Van Dyke brown. My tube is their old version from before they reformulated it to also have a small raw umber addition. Both of these Williamsburg paints have a large pigment grain and produce unique results that would be impossible to produce with modern imitations. Although they may look gritty in this photo, it’s not difficult to use them.

For comparison, M Graham’s paint here is a modern paint that has been given the name Van Dyke brown. Even if modern imitations are very similar in color they may be very different in handling, as you can see in how it has more uniformity and its covering power made it comparatively difficult to smudge thinly. In this case I think it’s due in part to the smaller particle size of the pigments used here. This paint was dry the first day that I checked the swatches, only about 24 hours after making them. That’s even though this is the only paint here that’s made with walnut oil, which normally takes a little longer to dry than linseed oil.

M Graham’s paint is itself an excellent paint, but there is a large difference between its handling and that of genuine Van Dyke brown. Whether this difference is an advantage or a disadvantage depends on the situation and the painting style.